-

The Science of Sourdough: Fermentation, Wild Yeast, and Flavor Development

At the beginning of the pandemic, just over three years ago, Google Analytics showed a huge increase in the amount of traffic generated from baking and cooking at home. You can see in the graph below that sourdough reached its peak popularity on Google searches just as the pandemic was gripping the nation. It makes a lot of sense too; people were desperate to find things that they could complete entirely in their homes, especially those that could reduce the number of items that were on a grocery shopping run and potential exposure to this new virus floating around. Now, sourdough recipes are appearing all over the internet, with burgeoning food blogs displaying their new bakes’ beautiful designs and perfect pairings. But what is happening behind this explosion of sourdough in the kitchens of the home baker? We’ll delve into the science of what gives sourdough that distinct flavor and some tips on how you can get started at home yourself.

Starting Starters

Sourdough contains a very simple set of ingredients: flour, water, and salt. That’s it! For a loaf that tastes seemingly so complex, the process requires a very small amount of input factors. However, sourdough’s leavening factor makes it unique. Rather than using a typical commercial yeast that you can buy from any grocery store, sourdough utilizes a fermented culture of flour and water, also known as a starter. This starter begins with equal parts flour and water by weight (it’s recommended that you use unbleached flour, such as the King Arthur brand to avoid any possible issues with starter forming) that comes in contact with natural yeast.

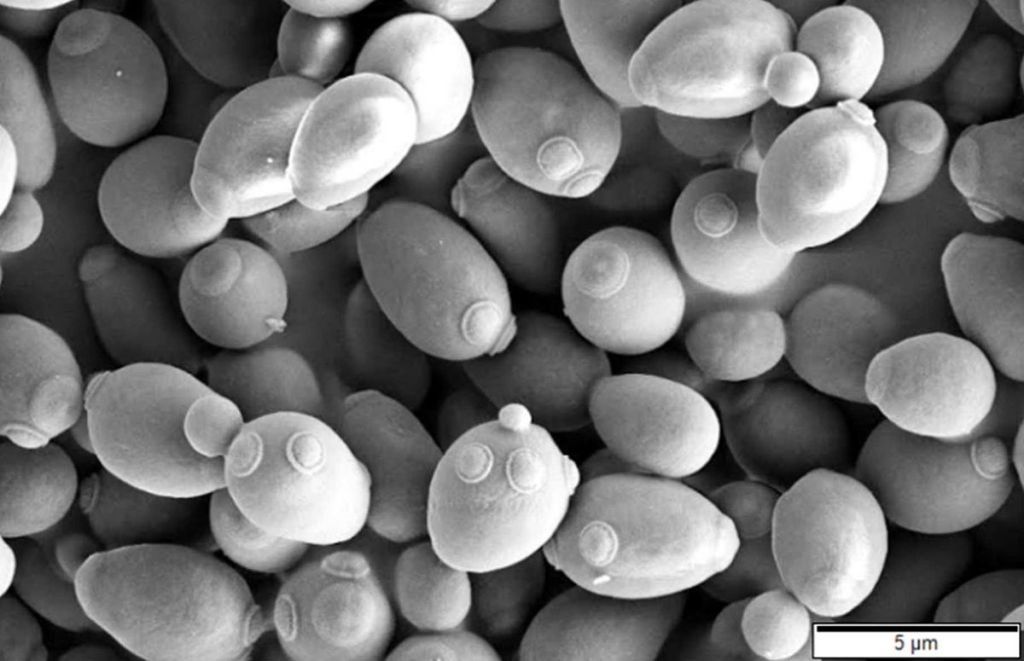

***Natural yeast, also known as wild yeast, are natural multi-micro flora that becomes seeded in a dough that has been left exposed. These are the basis of starters and bread across the world, as the yeast that generates in a starter dough is typically the same worldwide. Most yeast in these starters is a strain of the species Saccharomyces cerevisiae, with some other yeasts and lactic acid bacteria. These varieties of organisms that exist with S. cerevisiae are typically what give the sourdough its flavor. Lactic acid bacteria give sourdough a yogurt like flavor, while acetic acid-producing bacteria give it more vinegary notes**

Natural yeast are single-cell organisms that are incredibly useful in baking and fermenting projects, as they break down the sugar and starches in dough and convert them into carbon dioxide and ethanol. They are also what give beer its bubbles and alcoholic content. The yeast converts the sugar into carbon dioxide and ethanol through a process called anaerobic respiration, which means that it does not need oxygen in order to complete the reaction. Glucose, or the sugars present in the flour, are broken down by glycolysis (literally meaning “sugar decomposition”) which produces 2 carbon dioxide molecules, 2 alcohol (ethanol) molecules, and 2 energy molecules. The process is written below in scientific notation:

C6H12O6 → 2CO2 + 2C2H6O + 2ATP

This is why when we watch our starters grow and form over the first couple of days, we begin to see bubbles form and pop throughout the mixture. Carbon dioxide is formed via the yeast’s breakdown of the sugars and starches. The starter can also begin to form the ethanol that comes from the reaction in large enough amounts to be seen. This is called “hooch” and means that your starter needs to be fed again. While it wouldn’t be the worst thing to ingest the hooch that is coming from your starter, it is recommended that you pour off any hooch that has formed before feeding your starter again. But that is getting ahead of ourselves.

For an easy starter, mix sixty grams of unbleached flour and sixty grams of warm water, about one-half cup and one-quarter cup, respectively. Mix the two ingredients until it becomes smooth and thick. Cover the mixture in plastic wrap or a lid if mixing in a jar and let sit in a warm spot for around 24 hours. After this time, this is when we are inspecting for the bubbles mentioned earlier: we want to make sure that our starter has begun to ferment, which is indicative of yeast having come in contact with our mixture. Rest the mixture for another twenty-four hours, and don’t worry if there are not any apparent bubbles. Sometimes starters need a bit more time, especially depending on the type of flour you used to start. After day two, this is when we typically see the presence of hooch. Again, this means that our starter is “hungry” and needs to be fed again. Remove around half of the mixture in the vessel you are using and replace it with a “feeding” of sixty grams of flour and sixty grams of water. It will begin to rise and create more bubbles throughout the culture, and once its falls, it is time to feed the starter again. Usually, after a week from beginning the process, the starter will be doubled in size and its texture will be spongy and soft. It also should begin to smell a bit like yeasty bread. If it smells like alcohol (or some describe it as stinky feet), it means that your starter is underfed and needs some new flour. If all is well, your starter can be transferred to a new clean dish and you are ready to bake!

***NOTE: Some starters can be ready in a week, while others can take up to ten to fourteen days to complete. Once you have seen the activity begin to diminish and the texture is described as above, your starter is ready to use***

Anatomy of Bread

Sourdough and other breads all have the same anatomical structure: crust and crumb. The crust is formed as the starches in the dough begin to absorb moisture from within the bread and the oven atmosphere. As they gain more moisture, they eventually reach a breaking point, liquifying the starch and becoming a gel on the outside layer of the bread. A higher moisture content on the bread surfaces directly correlates to a crisper crust, as there is now a larger quantity of this starch gel on the bread. The caramel color of the crust comes from the Maillard Reaction, which was talked about more in-depth in an earlier post. The rigidity of the crust also comes from the coagulation of gluten molecules (which before was what gave bread its elasticity).

The crumb is the interior of the bread or anything that is not the crust. The water and flour that are used throughout the baking process are the greatest determiners of the final crumb structure. In the initial mixing, gliadin and glutenin (proteins available in the flour) combine to create the gluten that helps trap gases during the baking process. The more available gluten means a higher likelihood of entrapped carbon dioxide within the viscoelastic structure of the bread. The particular carbohydrate fermentation that occurs to provide this carbon dioxide is called the tricarboxylic acid cycle. The equation for fermentation is the same as the one listed above. Fine texture crumb is described as thinner walls between the open cells of the bread, while coarse is for larger cell walls. Breads that have higher water contents or lower salt contents are likely to experience very large cells, like a Swiss cheese slice.

Flavor Development

Flavor development of a sourdough loaf occurs at all stages of the baking process. The types of flour, whether rye, whole wheat, barley, or more, can impart the particular flavors that accompany those whole grains. Buckwheat flour makes a vinegary starter, whereas amaranth flour is toasty, and sorghum is a more fermented, yeasty smell. You can also have a drastic change in the sourdough flavor based on the bacteria that become entrapped in the dough during the initial starter phase. Starters with lower water contents, also known as “stiffer starters,” can encourage the lactic acid bacteria to create a sharp acetic acid taste, similar to vinegar. Higher water content, or runnier, starter? The lactic acid bacteria give a smoother, creamier tang to the bread compared to the sharp acetic acid. Fermentation of the starter in a warmer kitchen makes lactic acid bacteria create a sourer dough, but cooler temperatures (like storing your starter in the fridge) allow the yeast to produce a fruitier flavor.

Sourdough has been around for thousands of years, as the natural impregnation of yeast in sitting doughs has been taken advantage of since the times of the ancient Egyptians. With the more recent boom during the beginning stages of the pandemic, it has shown that we don’t need to always be buying a jar of yeast from the store in order to make delicious, fresh bread in our kitchens. Sometimes, with just a little flour, water, and salt, we can make science into tasty and beautiful creations.

-

Fascinating Fridays: Bromelain

One of my favorite fruits when perusing through the produce aisles is pineapple. Its funky almost pinecone-like shape and its sharp, rigid leaves belie the delectably sweet yet acidic golden pulp. After finally getting it home, the smell that wafts up from the cutting board elicits images of tropical salsa on chips and refreshing pina coladas while sitting on a warm beach. With my mouth watering watching freshly cut pieces falling from my knife, it takes almost all my willpower to make it to the end of prep to put a piece in my mouth. The wait has never been fruitless; that first piece that I get into my mouth burst with that far-away loved flavor, the juicy pieces instantly putting a smile on my face as I grab another and another. Soon though, I can feel my mouth getting sore, almost like I’ve been eating something incredibly hot or a very sour candy. The more pineapple pieces that I eat, the more intense this feeling becomes. What is causing this? How can something that smells and taste so sweet create a raw feeling like this in my mouth? The answer lies in an enzyme that is found in the pineapple, both in stem and the fruit: bromelain.

Bromelain is a group of active enzymes that is found in the pineapple plant’s fruit and stem. These enzymes assist in the breakdown of the proteins at their amino acid bonds. Depending on the protease that the enzyme may have, it breaks down the proteins at different parts of the amino acid chain. Serine (or the RNA structure AGU/UCG), cysteine (UGU/UGC), or threonine (ACU/ACC) are examples of some of the amino acids that are in a protein chain. Bromelain is a cysteine protease in particular, so wherever the amino acid chain contains a cysteine structure, bromelain will come in and conduct a proteolytical process.

A metric that should be noted of the bromelain that is in the fruit versus the bromelain in the stem is that fruit bromelain contains 90% of the “proteolytically active” material in the pineapple, meaning that the fruit of the pineapple contains 90% of the enzyme that feels like it is slowly dissolving your mouth (or tenderizing the proteins you may place in it). A protease, from proteolytic, is a “cleaver” of peptide bonds, which is also known as a process called hydrolysis. Hydrolysis is the breakdown of a water molecule into two parts, a positive H+ ion and a negative OH- group. In this particular reaction, the breakdown of the proteins is called proteolysis. In our bodies, we undergo proteolysis when we eat various protein sources, where we break down our foods into the amino acids that create them and then rebuild those amino acids into protein structures within our bodies. In the case of bromelain, it is accelerating in the breakdown of the protein in its vicinity, our mouths. This is why we begin to feel sore after eating a couple cups of pineapple. The bromelain is breaking the proteins or peptide bonds into the amino acids that, if coming from the foods that we are eating, we can create new proteins for the body to use.

***You may think this would exist in every iteration of pineapple in various dishes, but proteins have a tendency to denature (or breakdown) under heat. Most enzymes denature at around 55 degrees Celsius, or 130 degrees Fahrenheit. Bromelain denatures at 158 degrees Fahrenheit, which is slightly below the recommended consumer cooking temperature for eggs, rabbit, or red meat cooked at medium (160F). This explains why cooked pineapple is sweet without so much of the bite that comes from the freshly cut pieces***

Bromelain is a enzyme that is not at the fore front of everyone’s mind, but does play a crucial role in a meat/protein tenderizer for many recipes. When you look at a meat tenderizer like McCormick in the grocery store, bromelain is the hidden wonder in that powder boosting the tenderizing power. So, whenever you are enjoying the slice of pineapple on your pina colada and feel like small bite back, hopefully you give bromelain a brief bit of appreciation during your vacation.

-

Fascinating Fridays: Caffeine

Caffeine. One of the few substances on Earth that I am sure most people say they could not do without. Whether it is coffee, energy drinks, teas or just munching on a handful of chocolate-covered espresso beans, it is being taken in by roughly 90% of the world’s population on a daily basis. This beats out the 29% that drink alcohol or the 25% of the world population that uses nicotine. It also makes coffee the most consumed psychoactive drug (and the most socially acceptable one). In this Fascinating Friday, we delve into the way that our body takes in caffeine and its physical and psychological effects.

Caffeine is classified as a stimulant, meaning that it increases the activity of the central nervous system and the body in general. Specifically, it falls in the methylxanthine class of stimulants, which is joined by similar substances, such as theobromine (interestingly both found in chocolate and synthesized by the human body after ingesting caffeine) and theophylline (which is found in teas like yerba mate and the kola nut). In its pure form, it is a bitter, white crystalline powder. It is closely related in structure to adenine and guanine, which are two of the base nucleotides in our DNA and RNA. In the brain, there is a large nucleotide molecule called adenosine, which uses adenine as a base when is attached to a sugar molecule, ribose. You may have heard of adenosine in your school biology classes, where it was commonly represented in the compound adenosine triphosphate or ATP, the energy storage molecule of the body. Because caffeine is similar to this prevalent molecule in our bodies, it has an increased ability to bind to the same receptors in the brain. This means that it inherently blocks the ability of adenosine to bind to their receptors, but also increases the base nerve activity. This is what gives you those coffee jitters, leaving you feeling more awake and energetic.

The effects after intaking caffeine happen quickly, potentially due to the similarities of its chemical makeup and our base DNA nucleotides, and the effects on the human body can be felt within an hour of taking the substance. It is fairly soluble in its pure form, with water at body temperature being able to absorb around 20g/L before being too saturated to absorb more. However, with an increase in water temperature (at most to just below boiling) and the presence of an acid (which coffee beans provide), the solubility increases greatly. By the time you are taking your first sip of a freshly brewed cup of coffee, the new concentration of caffeine can be up to 660 g/L. In comparison, salt placed in nearly boiling water can only take in 359g/L before dropping out of the solution. Caffeine affects the CYP1A2 enzyme, which is a primary enzyme in the detoxification of the body, found primarily in the liver. This can result in a change in the efficacy of certain medications, as routine caffeine intake can result in up to a 20% decrease in the CYP1A2 enzyme efficacy.

***For a real-world example, coffee is shown to reduce the efficacy of escitalopram oxalate (more commonly known as Lexapro) by 28% in human trials. It also affects the intake of necessary vitamins and minerals. Iron absorption after caffeine intake can be decreased from 39%-90% after a single cup of coffee. Conversely, some medications have higher concentrations in the body after caffeine intake: taking a 650mg tab of aspirin with caffeine (120mg, or a cup of coffee) shows a peak of ~60 micrograms per milliliter vs. a peak of ~45 micrograms per milliliter, an 33% increase.***

The physical effects of caffeine show that it can increase performance in aerobic sports, especially those that require prolonged endurance. These athletes show delayed symptoms of muscle and central nervous system fatigue, meaning that they can operate for longer at that increased effort level before needing to take a break. For individuals that are considered to have lower physical fitness, it is shown to have an increased effect on the oxidation of fatty acids, meaning that it breaks down fat quicker. This happens due to the increase of hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL and an enzyme that breaks down fats) and inhibits glycogen phosphorylase (which is the enzyme that is used to break down polysaccharides or carbohydrates in the body. Because of this, there are higher levels of glycogen in the muscles after exercise, which means the body can potentially recover energy faster as these carbohydrate stores have not been depleted. Because of these potentially performance-enhancing aspects of caffeine, it was placed on the World Anti-Doping Association ban list from 1962 to 1972 and 1984 to 2003. It was removed in 2004 but is still monitored by the WADA because of its potential for misuse during competitive sports. Caffeine also causes diuresis, or excessive urination, which is a direct effect on the kidney at the adenosine receptors (similar to the effects in the brain).

Psychological effects of caffeine can range from person to person, depending on their particular caffeine sensitivity, but usually fall into general symptoms. In the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, it was shown that caffeine had been associated with decreased depressive symptoms and overall suicide risk. It also can increase alertness and increase emotional arousal (most noticeably in low caffeine users). However, it can work inversely. In larger doses or more sustained use, it has been shown that caffeine can increase anxiety-related symptoms, such as faster breathing, headaches, and increased sweating/pulse rate, and was placed in the DSM-5 as a subclass of Substance-Induced Anxiety Disorder (look for caffeine-induced anxiety disorder). It has also been classified as a potential cause of sleep disorders (reducing the slow-wave sleep in the early sleep cycle as well as a reduction in REM (rapid eye movement) sleep), eating disorders (increasing the metabolic rate and suppressing appetites) and possibly schizophrenic disorders (the adenosine receptors in the brain and the control of dopamine release).

Caffeine is a ubiquitous substance in our daily lives, and has helped many people with school, work, sports and more. But it is important to know the pros and cons of caffeine usage, no matter if you are casual tea drinker or downing multiple espresso shots before shooting out for the day. Always take all foods in moderation.

-

Fascinating Fridays: Flavor Pairing

This week with Fascinating Fridays, I wanted to delve into the world of food pairings and the chemical science behind what makes certain flavors meld perfectly and others have such adverse tastes. I remember as a kid also eating the funkiest, off-the-wall combinations that just seemed to work: scooping peanut butter with a cheddar cheese stick, my grandmother’s pepper on cantaloupe, honey on slices of pizza from the local Mellow Mushroom, and more. My father was also a huge proponent of different flavor combinations, always putting dabs of olive oil on vanilla ice cream or making his signature Tuna Steaks and Waffles (which quickly became a mainstay in our household when I was a kid). From the outside, we all might hear these combinations and visibly cringe at the thought of letting them anywhere near our mouths, but once we take that leap of faith, they showcase flavors that aren’t appreciated when trying the singular food components on their own.

We probably all remember back in grade school the diagram of the tongue and the divisions “dedicated” to tasting different flavor profiles of foods. These profiles are sweet, bitter, salty, sour, and umami, which was assigned in the 1980s after researchers debated about whether it could be considered a base flavor profile. Taste was thought to be relegated to these regions of the tongue after a research paper by German scientist David Hänig was published in 1901. The region theory was further entrenched into educational systems after Edwin Boring, in the 1940s, created the graphic that we all were presented in school. This map design was contentious between much of the sciences around the human body, with some doctors going as far as cutting or anesthetizing the nerve that runs to the end of the tongue in an attempt to eliminate the sweet taste bud receptors. These doctors found that not only did patients that had certain regions of the tongue’s sensory nerves cut not lose their sense of tasting sweet foods, but in some patients, it actually was stronger. Further studies into the science of taste showed that our tongues’ taste receptors were able to pick up on the various flavor molecules anywhere on its surface, allowing us to completely taste foods uninhibited by the position in the mouth. Other factors also contribute to what we taste: temperature (where some people may prefer to have their fruit in the fridge or on the counter), texture (preferring to cook vegetables or eat them raw), and visual stimuli (studies have shown that people who drink white wine that has been dyed red would note flavor profiles that are specifically found in red wine).

Researching the chemical makeup of the common food flavors and scents that we enjoy in our daily lives was daunting. In one database alone, over 25,000 molecules were documented and categorized that showed the breakdown of more than 2000 aromas and tastes. Foods themselves are also made up of a combination of these various flavor molecules, with can reach up to 800 or more unique chemicals in foods like coffee beans. What allows for more precise flavor pairing is this specific chemical makeup that different foods have. The more flavor molecules that a particular food has in common with another, theoretically the better those foods will taste when put together. For example, brussels sprouts have 110 molecules in common with broccoli, such as delta-cadinene which produces woody or thyme-like flavors, and epicatechin for more bitter flavors. It makes sense if you think about it; broccoli and brussels sprouts come from the same family of vegetables. But it also shares 104 with mangoes, including 2-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)Ethanol’s floral profile. This means that a mango chutney on roasted brussels sprouts has the potential to be on par in terms of personal agreeability as a skillet of pan-roasted broccoli and brussels sprouts. My father’s Tuna and Waffles? While you may be hesitant to try it, the waffle shares 3 flavor molecules with the tuna, which is the same amount that it shares with maple syrup. Pepper and cantaloupe? 105 flavor molecules. Olive oil and vanilla ice cream? 108.

**Note** – placing flavors together based on their chemical makeup does not mean that the new combination will automatically become a winner. It just offers a good starting point for experiments in food tasting.

The science behind the combination of different foods based on their chemical components is called flavor-pairing theory, which has created a movement in the cooking community and spawned businesses dedicated to this science. Chefs from different disciplines and cuisines, such as East Asian, North African, and Pan-American cultures, have applied the flavor-pairing lens to their dishes and determined what it was that has made their foods staples in the community. They began to break down their dishes again into the basic flavors that we were taught in school and showed that certain compounds were determining how our brains would interpret the taste. Phenolic compounds were present in higher numbers for foods that testers would say were bitter. Citric, malic, lactic, and tartaric acids put sour tastes in our mouths when we eat fruits or yogurts. Sweet foods were higher in the -ose molecules, such as fructose and lactose. In the 80s, when they designated umami as a basic flavor, they were seeing that foods with increased levels of glutamate were being picked out more to describe that new savory flavor. People, who had been naming their favorite foods as salty or savory, sour or sweet, now were being shown that their preferences were containing higher amounts of the particular molecules and that there was hard scientific data behind the flavors that they were experiencing.

While we could research the chemical compound of our shopping list to determine the best food to pair with our next home-cooked meals, it isn’t feasible, and it also takes the fun out of experimenting with our purchase choices. There are quick, internet-free choices that we can make on the spot when knocking our watermelon or grabbing our milk from the refrigerator to help find a close pairing to experiment with:

- Fatty dishes, such as those with oil-based pasta sauces or avocados, work well with acidic foods, like adding wine to a simmering dish of beans.

- Spicy foods are countered well with starchy or fatty foods (which is why you were always told as a kid to go for milk and not a glass of water).

- Salted caramels work well because salt added to a sweet dish can cut the sweetness that is received by your taste buds. This also works the other way around, as sweet potato casserole demonstrates well.

If you are interested in looking at one of the databases featured in this post, FlavorDB is a fantastic resource. Comprehensive, yet user-friendly, it provides an in-depth look at the multitude of molecules responsible for some of our favorite foods. There is also a Belgian company that started a blog called Foodpairing specifically dedicated to the science of food pairing and has history lessons and recipes intertwined within all of their posts. And one final fact: from extensive research and cross-references, it is scientifically shown that the flavor profiles of pineapple and pizza (specifically the cheese for pizza) do not go together. Personally, I’ll just pretend that I didn’t see that one.

-

Fascinating Fridays: The Maillard Reaction

I have a deep love for food and science, and recently I began exploring the connection between the two. How do salt and sugar preserve foods? What creates a bitter taste when foods like garlic cook too long? So many questions pop into my head when slicing vegetables or sauteing over the stove, and I’m sure that we all have had those nagging questions that linger long after our plates are cleared. When recently testing out making oyster mushrooms into mock scallops, I became mesmerized watching the browning occur along the cut edges of the fungi. “What is making it crisp so uniformly? Why does it form a crust in some areas but merely heat the mushroom in others?” With these questions in the back of my mind, I poured into food science articles and videos of chefs flipping French toast and came to find that the science behind this browning has been studied extensively and practiced for as long as we’ve harvested grain. This is the Maillard reaction.

The Maillard reaction is a chemical reaction of the proteins and sugars in a particular food. Unlike caramelization of sugars, or pyrolysis (grilling or toasting of foods where “burnt” portions develop), very specific temperature ranges are needed to begin the rapid process of the Maillard reaction. This range is set between 140 and 160C (280-350F) and is what begins the process that gives us that golden brown, crisp texture on the outsides of our bread and fried foods. The precise science is the carbonyl group (a molecule that contains a carbon and oxygen atom connected via a covalent bond (double-bond)) from the sugar reacts with the amino acids in the food, creating a biochemical compound called glycosylamine and water. Glycosylamine is inherently not stable, so it rearranges itself to become a ketosamine, a more stable molecule that further develops into nitrogenous polymers and melanoidins, the polymers that give food that deep brown color.

The Maillard reaction is not only the reason behind the browning that you see on bread or meats (or even that rich smell of coffee percolating) but also the chemical reaction behind the smells that waft from bakeries and out of your rice cookers. The compound 6-Acetyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydropyridine is the specific aroma compound that gives bread, tortillas, and other baked items that distinct just-out-the-oven smell. This compound can only be synthesized via the Maillard reaction, which is why mixed/rising dough smells more yeasty and less “fresh-baked”. Almost all of the reactions in the oven that makes bread look and smell so delicious are known to us now due to Louis Camille Maillard, the namesake for the reaction.

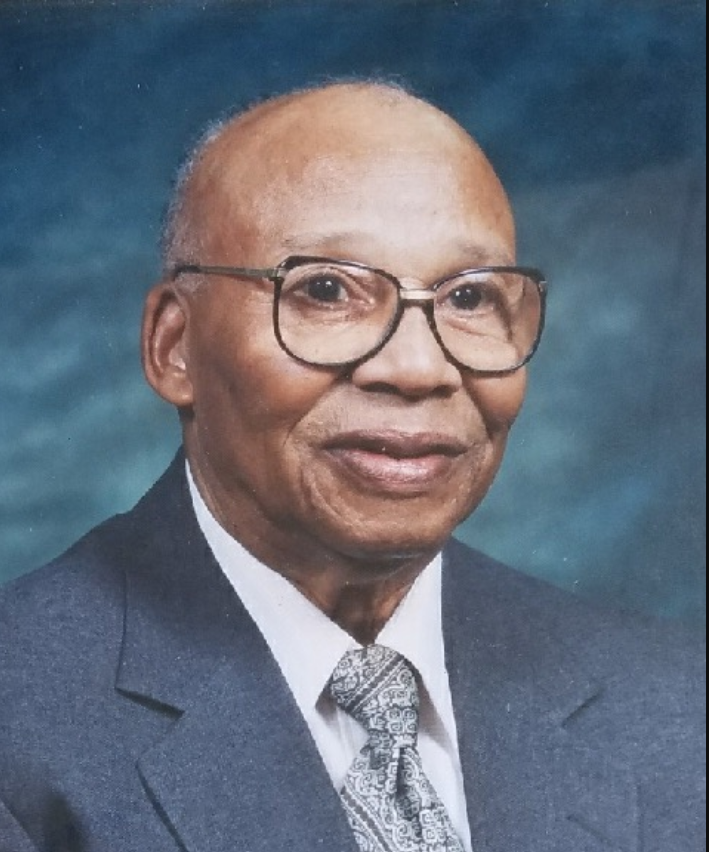

Louis Camille Maillard was a French chemist and physician. He primarily worked in the nephrology field, dealing with various ailments of the kidneys, but took interest in the presentation and reactions of amino acids and sugars, especially in foods. He began laying the groundwork in the 1910s for the cause of browning and flavor profile changes in cooked foods but was not the one who ultimately discovered the mechanisms that are described above. That distinction falls to an African American chemist named John E. Hodge. Hodge worked for the United States Department of Agriculture and in 1953 discovered the way that the sugars react with the amino acids, releasing the glycosylamine that undergoes the Amadori rearrangement to produce the browning compounds.

More scientists have delved into the scientific processes involving the Maillard reaction, and have found that even on molecular levels within our bodies the reaction occurs. Sugars that are floating around our blood after eating start Maillard reactions in the form of inflammation responses particularly centered around the cardiovascular and liver systems. Our bodies have developed defense mechanisms (aside from the inflammation response) to remove the by-products of the Maillard reaction, but are effective only up to 99.7% of the time. Those reactants that slip under the fence can begin to cause more serious damage to our bodies over time (for example, cardiovascular disease).

Ultimately, as I sear another mushroom on the stove, I am happy to know a little more about the process that gives my mushrooms that nice crunch and fills my apartment with the smells of a Parisian bakery during weekend afternoons. Just like Maillard over 100 years ago, cooking continues to fascinate and delight people around the world, just like me in my kitchen. I plan to continue these little scientific forays into food once a week and would love to hear some questions from those that are reading that may have popped up when in your kitchens. Always have fun and try to push your boundaries when working in the kitchen, stepping out of your comfort zone and trying a new cooking method or food from a different part of the world. Let me know your new experiences and I’ll see everyone for the next Fascinating Friday where we’ll talk about flavor profiles and why certain foods match so well with others!

-

Karman Kitchen Beginnings!

I decided to start this blog as an attempt to document the different baking and cooking projects that I frequently dive into. My girlfriend, Michelle, and I have cooked various cuisines inspired by India, Eastern Europe, and Latin America, but we both found abundant love and kitchen creativity in becoming vegan. We both are working on becoming more environmentally conscious as well as health-conscious, and starting a vegan lifestyle was the next logical step. We have been working on it for the past couple of months, and have been taking much inspiration from Vegan Soul Kitchen and Vegan Richa’s Instant PotTM Cookbook. Other forms of inspiration have been some local Seattle restaurants or old non-vegan fast food favorites. I hope that this blog can be a source of inspiration for each of you that is reading now; a growing repository for vegan/environmentally focused cuisine as well as a community board for your tips and tricks!

I decided on the name “Karman Kitchen” off of the Karman line, the usually agreed-upon point at which our atmosphere ends and outer space begins. I have had a deep love of space since I was in high school, and always had a sense of wonder and longing when gazing at the stars or feeling like a school kid seeing the launches of new satellites and rockets over the last couple of years. I wanted to emulate the level of wonder and awe that I have when staring at the sky in the food that I cook, so I created “Karman Kitchen” as a personal goal to myself to create food that recreates that for my family, friends, and now you!

Starting this blog post, I wanted to come from a place of familiarity and ease. One of Michelle and I’s “frequent flyer” spots when making the switch from eating meat to becoming more plant-focused was Taco Bell. We usually grabbed bags of bean burritos (“Fresco Style” of course!) and Diablo sauce and be perfectly content. On one of our trips through the drive-thru, Michelle and I reminisced about the crunch wraps that Taco Bell sells and how much we missed getting that iconic meal. During our meal prep for the week, we decided to come up with our meatless version of the crunch wrap, and it instantly became a favorite recipe!

All vegan and delicious, the main protein base is lentils with a hearty amount of cumin, chili powder, and smoked paprika. Lentils should be prepared per the package: sorted and rinsed, making sure that no stones are in the lentils. They are placed in a pot of cold water and brought up to a boil. Once boiling, reduce the lentils to a simmer and cover for twenty to thirty minutes, or until tender. Once the lentils are cooked, strain them and place them to the side. Half a yellow onion and 3 cloves of garlic are cooked down for eight minutes, after which the lentils are added to the cooked onions. The cumin, chili powder, and smoked paprika are added to the lentil mixture at this time, as well as salt and pepper to taste. Remove the cooked mixture and place to the side and grab the rest of your crunch wrap ingredients. First, with your burrito tortilla, place around a quarter cup of the lentil taco mixture and a slice of vegan cheese on top of the lentils. Next, grab your tostada and place it on the cheese, following up with a smear of vegan sour cream over the tostada. Finely chop a couple of slices of onion and cucumber and mix with your favorite salsa, placing the mixture on top of the sour cream. Lastly, you’ll want to wrap the edges of the tortilla over the fillings and place folded side down on a skillet over medium heat. Cook for around two to three minutes (or until golden brown) and flip. Cook again until golden brown on the top and promptly remove from the heat. Serve with lime, your favorite salsa or guac, or maybe even some Diablo sauce from Taco Bell!

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.